Redefine Success in Dance

It All Begins Here

Confidence doesn’t always arrive with a bold entrance. Sometimes, it builds quietly, step by step, as we show up for ourselves day after day. It grows when we choose to try, even when we’re unsure of the outcome. Every time you take action despite self-doubt, you reinforce the belief that you’re capable. Confidence isn’t about having all the answers — it’s about trusting that you can figure it out along the way.

The key to making things happen isn’t waiting for the perfect moment; it’s starting with what you have, where you are. Big goals can feel overwhelming when viewed all at once, but momentum builds through small, consistent action. Whether you’re working toward a personal milestone or a professional dream, progress comes from showing up — not perfectly, but persistently. Action creates clarity, and over time, those steps forward add up to something real.

You don’t need to be fearless to reach your goals, you just need to be willing. Willing to try, willing to learn, and willing to believe that you’re capable of more than you know. The road may not always be smooth, but growth rarely is. What matters most is that you keep going, keep learning, and keep believing in the version of yourself you’re becoming.

5 Partnering Principles Every Ballet Teacher Must Understand

It All Begins Here

Introduction

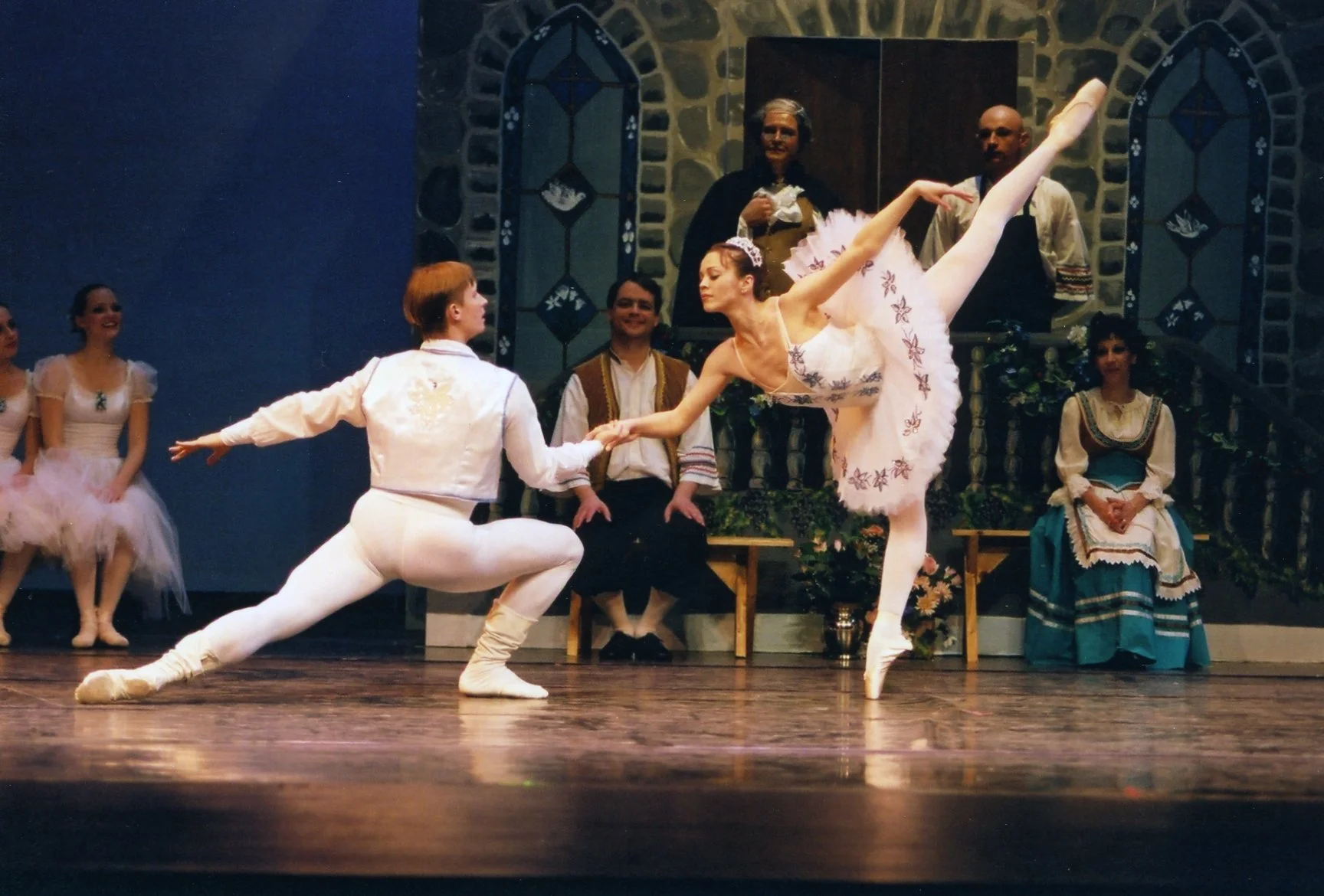

Partnering in classical ballet is often introduced too late, taught too quickly, or approached as a collection of tricks rather than a structured discipline. In reality, correct partnering grows directly from classical technique, coordination, and musical understanding developed long before two dancers touch.

This short guide outlines five essential principles every ballet teacher should understand before introducing or refining partnering in class or rehearsal. These principles are rooted in the classical tradition and aligned with Vaganova-based pedagogy, emphasizing clarity, progression, and responsibility from both partners.

This is not a substitute for full training, but a foundation.

Principle 1: Partnering Begins in Classical Positions

Partnering does not start with lifts. It starts with how dancers stand, move, and coordinate their bodies in classical positions.

Incorrect placement, unclear épaulement, or weak coordination will always surface more dramatically in partnering than in solo work.

For Teachers: - Ensure students can clearly execute positions of the arms and body in motion - Demand clean preparation before any partnered movement - Do not excuse technical errors because a partner is present

Partnering reveals technique — it does not replace it.

Principle 2: Coordination and Timing Are Shared Responsibilities

One of the most common teaching mistakes is assigning musical and technical responsibility to only one partner.

Both dancers must: - Hear the music - Prepare together - Complete movement together When coordination is unequal, partnering becomes unsafe, heavy, or rushed.For Teachers: - Teach timing verbally before physical contact - Rehearse preparation without touch - Insist that both partners initiate movement consciously

Principle 3: Strength Is Secondary to Organization

Strength alone does not produce clean partnering. Proper alignment, counterbalance, and efficient use of weight do. Many injuries and technical problems arise when dancers attempt to compensate with force instead of organization.

For Teachers: - Delay complex lifts until students understand weight transfer - Emphasize clarity of pathway over height - Correct posture and placement before increasing difficulty

Well-organized partnering appears effortless because it is efficient.

Principle 4: Progression Is Non-Negotiable

Partnering must follow a logical progression, just like classical technique. Skipping steps leads to: - Poor habits - Fear and tension - Increased risk of injury

For Teachers: - Introduce partnering first through supported balance and simple coordination - Avoid choreography-driven partnering before technical readiness - Repeat foundational exercises regularly

Partnering taught without progression becomes imitation rather than education.

Principle 5: Knowing When Not to Partner

An often-overlooked skill is recognizing when partnering should be delayed or removed entirely. Signs students are not ready: - Loss of individual technique - Rushed preparation - Dependence on the partner for balance

For Teachers: - Remove partnering if technique deteriorates - Return to solo work when necessary - Reinforce independence within partnership Good partnering preserves classical standards — it does not lower them.

Closing

Partnering is not an accessory to ballet training. It is a discipline that demands the same structure, clarity, and respect as classical technique itself.

For a complete methodology, detailed progression, class applications, and

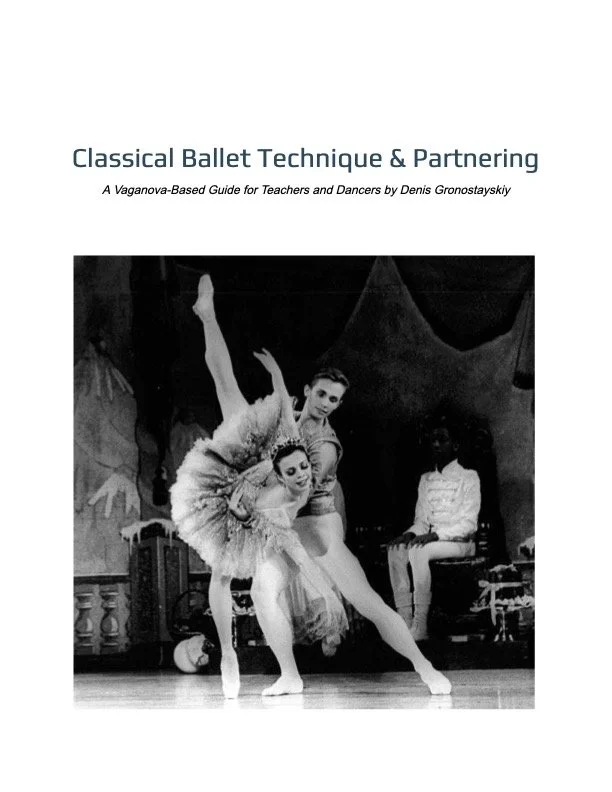

professional-level guidance, see the full book: Classical Ballet Technique & Partnering

Chapter 1: The Purpose of Classical Positions

It All Begins Here

Understanding Positions as Living Coordination, Not Static Shapes

Classical ballet positions are often taught as fixed forms: where the feet should be placed, how the arms should appear, and what the body should resemble when movement stops. While this visual clarity is important, it represents only the outer surface of classical technique. In reality, positions are not static shapes but moments within continuous coordination.

A position in classical ballet is a point of organization through which movement passes. It is never an end in itself. When positions are treated as poses to be held rather than systems of coordination to be lived, dancers lose flow, musicality, and functional control—issues that become even more apparent in partnering. Each classical position integrates the entire body: feet, legs, torso, arms, head, and focus. The placement of the feet alone does not define first, fifth, or any other position.

The position exists only when the body is coordinated, balanced, and oriented with intention. Without this integration, the position becomes decorative rather than functional.

For teachers, the responsibility is to move students beyond imitation. Students must understand that positions organize weight, prepare direction, and establish readiness for the next action. In this sense, positions are verbs rather than nouns. They act.

In partnering, this understanding is essential. A partner does not respond to a shape; they respond to intention, preparation, and coordination. When a dancer arrives in a position without clarity or readiness, the partner has nothing reliable to work with.

Conversely, when positions are alive with coordination, partnering becomes clear, efficient, and secure. Teaching classical positions as living coordination establishes the foundation upon which all advanced technique—and all successful partnering—is built.